Book Review : Visionary Fiction

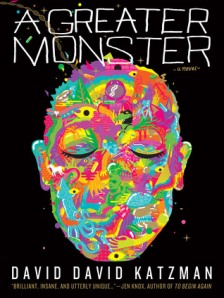

A Greater Monster

Editor's note: Here is a review of A Greater Monster, by David David Katzman. This book is the recipient of the Independent Spirit Award, one of the 12 Outstanding Books of the Year chosen during the 2012 Independent Publisher Book Awards from 5,203 entries. The review first appeared in PsypressUK.

* * * * *

Originally published in 2011, A Greater Monster is the second novel by Chicago author David David Katzman; his first being Death by Zamboni. The book’s blurb describes it as “Innovative and astonishing… [breathing] new life into the possibilities of fiction” and, without doubt, the novel lives up to this description: A psychedelic journey into the splintered mind of a life on the desiring edge.

The title of this novel is taken from a line written by the philosopher and essayist Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592): “I have never seen a greater monster or miracle in the world than myself.” The cover illustration, by Mike Wilgus, reveals the depths to which the unnamed protagonist’s ‘greater monster’ is inhabited by a multitude of characters, motifs, colours and flows. A Greater Monster is the story of how these multitudinous, chaotic elements are played out through the immanent plane of the protagonist’s mind; the text exploring, with a touch of Alice in Wonderland, his psychedelic-esque discombobulation.

The story’s external coherence begins to ebb away with the protagonist working long hours in a sales office. He takes a black lozenge that he acquired at the very start from a shifty, homeless character who later, when re-approached, appears to know nothing of their previous encounter. Once taken, the effects on the protagonist’s mind, coupled with the existing flows of the man’s own daily-grind drudgery, explodes in waves of fear and desire: “[I] Popped it in my mouth. Tasted like chicken. No, hah. Tasted like bone and asbestos. Like death. I swallowed and gagged, but it went down. My tongue went prickly and started to burn as if I had eaten too much pineapple. I gasped as it oozed a trail down my throat, taking its time. Mistake. That was a mistake. Oh yeah, shit. Why’d I do that? Shit. I closed my eyes” (Katzman 2011, 6). Space and time quickly become the categories that are destroyed by the onset of his experience, revealing the rich patchwork of motifs that make up the novel.

“There are three emotional fields. The gravity of desire. The strong force of love. The electromagnetique force of fear. Desire is autonomatically attractive, requires the bringing of another into one’s orbit. Fear is both attractive and repulsive, driving objects apart or together. Currently (and I use that term ectomagnetically), the global forces of fear and desire are macrotically powerful, while the exclusionary force of love functions over subtle differences enclosing limited bodies” (Katzman 2011, 313).

The above quote, appearing toward the end of the book, gives some indication as to how Katzman’s chaotic and confused narrative is played out. Against a backdrop of desires, fears and love, the protagonist searches, often blindly, for recollections of his self that manifest as a forgetfulness, not only of his self, but also of humanity in a post-apocalyptic field of play. Near the beginning these flows kept him as a unitary being, literally holding him as one, as the desires of the external world are yet to be broken through: “I woke up in my new suit. It seemed to be holding me together so I left it on” (Katzman 2011, 25). However, the ‘desiring machine’, to use a Deleuzo-Guattarian term, begins to dissipate into separate flows and he becomes a body-without-organs.

The strange motifs and extravagant characters are a playful dance between Jungian and Freudian imagery, interspersed with paradox and pop-philosophy. A ‘longing after’ pervades the text, as strange anthropomorphised animals and objects, classical characters and personal bents are trundled out in a mish-mash text that, as a reader, is at once difficult to follow in its totality, yet intricately understandable in its minute parts. The grand narrative of a Greater Monster, can only be understood in the secondary mini-narratives, which although reflect one another to a degree, also diverge sharply across a single page. The reader, like the protagonist, wonders/wanders lost and unaware of self, history, body; a true textual discombobulation.

Use of traditional forms are completely done away with by Katzman. Paragraphs are set out for online reading (spaced by a whole line), yet even these break up as words are curled, re-spelt, splashed across the page, vertical, horizontal, enlarged and emboldened, not to mention the shifting narrative perspective. Most obviously this reflects the mayhem of the protagonist’s mind and the reader is led into a similar space by the challenge of Katzman’s new formats, word plays, and styles. Yet, for the seriousness of the undertaking, the book is not without its humour, when even the simplest use of synaesthesia can jolt you back out from the desires and fears: “Ow!” More surprised than hurt. My face smashed against the cabinet, his bony hand wrapped around my head. Strange, the wood tastes like gravy” (Katzman 2011, 105). The themes, and the emotions they are traditionally used to elicit, are mashed and cut-up through one another, making one’s response feel alien to the novel.

“Every life is a story, a song, a groove in the flow. Most beings think they’re stuck in one track. But you drank from the river of forgetfulness. Perhaps it threw you off your fated course, and you followed a new one, a quest that allowed you to move beyond the river that channeled you, and you begin to live other stories” (katzman 2011, 348).

In many respects, Kaztman’s book is a challenge for the reader. It is difficult to keep a long concentrated thread going when it is so obviously skipped within the text itself and, although this might be stylistically commendable, it does little favours for the pure pleasure of story. However, having said that, it is a novel one can pick up randomly, even at different places and in different times, and find the inner monsters most revealing; able to establish fleeting relationships, which the confusion of the protagonist acts as a strange mediator for. The novel is a trickster that one feels will be, like the fear it discusses, attractive and repulsive in and of itself for the reader. Perhaps, as all good trips should be.

* * * * *

About PsypressUK

Rob Dickins is currently the editor of the Psychedelic Press UK, and is undertaking an English literature research masters, with the University of Exeter. The topic of his thesis is the proliferation of psychedelic literature between 1954-1964, dealing primarily with texts on the psychotherapeutic use of LSD and other hallucinogens.